In 1989, Congress declared October Domestic Violence Awareness Month in an effort to bring more recognition to an often ignored and invisible trauma faced by up to 25% of the population. As the nation enters its thirty-fourth Domestic Violence Awareness Month, four UC Global Health Institute students are working to translate academic work into tangible positive impacts for survivors and those at risk.

While domestic violence may be more openly discussed than in the past, a common thread in the students’ research is that there is still plenty of need to raise awareness. A good start, suggests Dr. Jianchao Lai, who recently earned her PhD in the Department of Social Welfare at the Luskin School of Public Affairs at UCLA, might be by replacing the term “domestic violence” with the more inclusive term “interpersonal violence.” According to Dr. Lai, the shift, already occurring in academia, is necessary because the term domestic violence often invokes “heterosexual marriage, [that] the violence happened in that context.” Interpersonal violence, points to the fact that such violence may “include two people, or a group . . . or even a situationship [and other] nonmarriage relationships,” allowing non-heterosexual-marriage survivors to recognize their experience as domestic violence. Dr. Lai adds that this broader understanding encompasses a spectrum of behaviors “ranging from physical abuse... to verbal abuse, emotional abuse, even financial abuse” that can affect college students who may be with an abusive parent, guardian, family member, intimate partner, or roommate.

Dr. Lai grew interested in interpersonal violence while pursuing her masters of social work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison where she worked on a transmedia project to elevate survivors’ voices. She has continued her work with transmedia at UCLA with the research study, “Double Jeopardy,” where she is co-principal investigator. The “Double Jeopardy” study explores the Asian survivor experience, an area Dr. Lai grew interested in due to her own Asian identity and the rise of xenophobia and hostility aimed at Asians/Asian-Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic. She sees unique factors that contribute to a resounding silence around the issue in this group, such as the hierarchical nature of the family and emphasis on preserving its reputation.

An analysis of silence is at the center of Laura Castrillón-Guerrero’s research on sexual violence on college and university campuses. Castrillón-Guerrero has a background in psychology and a Master of Arts (MA) in cultural studies at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia. She also serves on the Student Advisory Board of the UCGHI Center for Gender and Health Justice’s Global College Campus Violence Prevention (GCVP) Network, which supports projects related to gender-based violence on university campuses worldwide. Castrillón-Guerrero is currently adapting her research into a graphic novel that centers the stories of survivors of gender-based violence, pointing out how violence affects their lives but also pushes to create ways of resistance and healing.

She has zeroed in on four silencing practices that colleges and universities use on survivors: censorship, tone policing, exhaustion (creating barriers to getting justice), and pretending to do the work. For Castrillón-Guerrero, real change requires more than “documents and protocols; it requires a lot of political will in high places [to create] a waterfall effect.” She emphasizes that survivors are more likely to go to student groups before they’ll go to university administration, which may see them as “just making noise.”

The stakes are high because the impact of the violence on survivors’ lives is huge, Castrillón-Guerrero says. It changes “the way you relate to others, your peers, to your family. Even the way you decide to go or stay in the university. Sometimes your academic trajectory changes.”

Ngoza Mubambe, who, like Castrillón-Guerrero, serves on the Student Advisory Board of the GCVP Network, and is a senior at the University of Zambia, is also interested in the way violence affects survivors. She sees them “detach themselves from society,” which she attributes partly to their being “filled with fear that they’re not safe.” To prevent such outcomes, Mubambe has used funds from the GCVP Network to organize a sports day at her university that included educational efforts on domestic violence for students. For Domestic Violence Awareness month, in a separate initiative, she is planning a workshop, “Strike and Thrive” that will teach college students physical self-defense techniques to escape and fight back effectively when caught in violent situations.

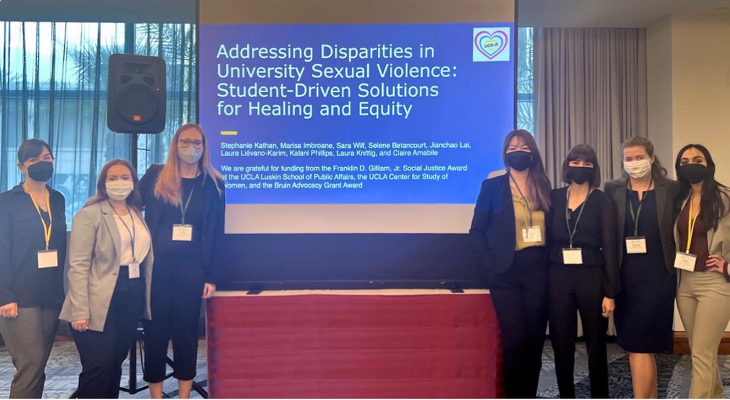

When prevention efforts fail, another issue comes to the forefront: resources for survivors. Even when they are available, as they often are on UC campuses, there can be obstacles to accessing them, says UCGHI Student Ambassador alumna, Kalani Kieu-Diem Phillips, who is a PhD student at UC Irvine studying public health. She cites the findings of a research study conducted over the last few years by the Survivors + Allies, a student group that Dr. Lai also belongs to at the UCLA campus. The study, whose creation both Phillips and Dr. Lai took part in, was designed to investigate UC affiliate (student, staff, faculty, and alumni) awareness and utilization of resources for survivors of sexual assault and violence on UC campuses with the ultimate goal of changing policy. Its findings, due to be published on the UCLA Center for the Study of Women website in January 2024, are currently being gathered into a report titled, “From Surviving to Healing: Results and Demands from a Study with Survivors of Sexual Violence on University of California Campuses.”

Phillips, who also earned her bachelor’s degree in public health policy and master’s degree in public health at UC Irvine, joined the group in part due to her own experiences as a survivor of domestic abuse and violence while in college. She found, to her dismay, that there has been little progress in improving awareness of and access to resources for survivors of sexual abuse and violence since her time as an undergrad student at Irvine. According to Phillips, a common obstacle UC students faced when seeking support from campus sponsored Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) after an assault was that it “would take them weeks to get an appointment, and if they do get an appointment with someone, that person may or may not have expertise in treating someone who is a survivor.” Sexual assault and rape treatment kits and sexual assault nurse examiners are not always available on every UC campus. While UC Irvine recently created a sexual assault forensic exam site on its campus, most UC students are forced to travel an average of 12 miles to obtain a forensic exam. As a student, “How likely would you be to call an Uber right after something like that happens to go get a rape kit?” Phillips asks. Many students also reported negative experiences with Title IX offices.

Based on the Survivors + Allies findings and recommendations report, Phillips thinks the University system needs better outreach to ensure that students know about resources that are available to survivors of violence as well as to invest in better training for both students, faculty and staff regarding reporting, “because a lot of students reported having bad experiences with faculty and staff when they [do] share what happened to them.”

Knowing how to support survivors of interpersonal violence can be challenging to friends and family, too. Drawing on “From Surviving to Healing,” Phillips recommends, “Be an active listener and believe them, be open and support them and respond to what they need. Express admiration for their courage, ask them what you can do to help. And then take care of yourself and practice self-care as well. Because I mean, they're probably going to tell you something really heavy.”

We invite our UCGHI community to engage in open dialogue and learning opportunities this Domestic Violence Awareness Month to better support ourselves and others, to critically evaluate how we can better promote healthy relationships across the UC, and to understand how interpersonal violence intersects with other global health issues.